I was midway through a system-design talk when a familiar question landed:

So… is DDD an architecture or a pattern?

The room had many .NET folks. Heads tilted. Some smiled the “here we go” smile. Let’s answer it simply, and then go a little deeper; without buzzword gymnastics.

A simple definition of DDD

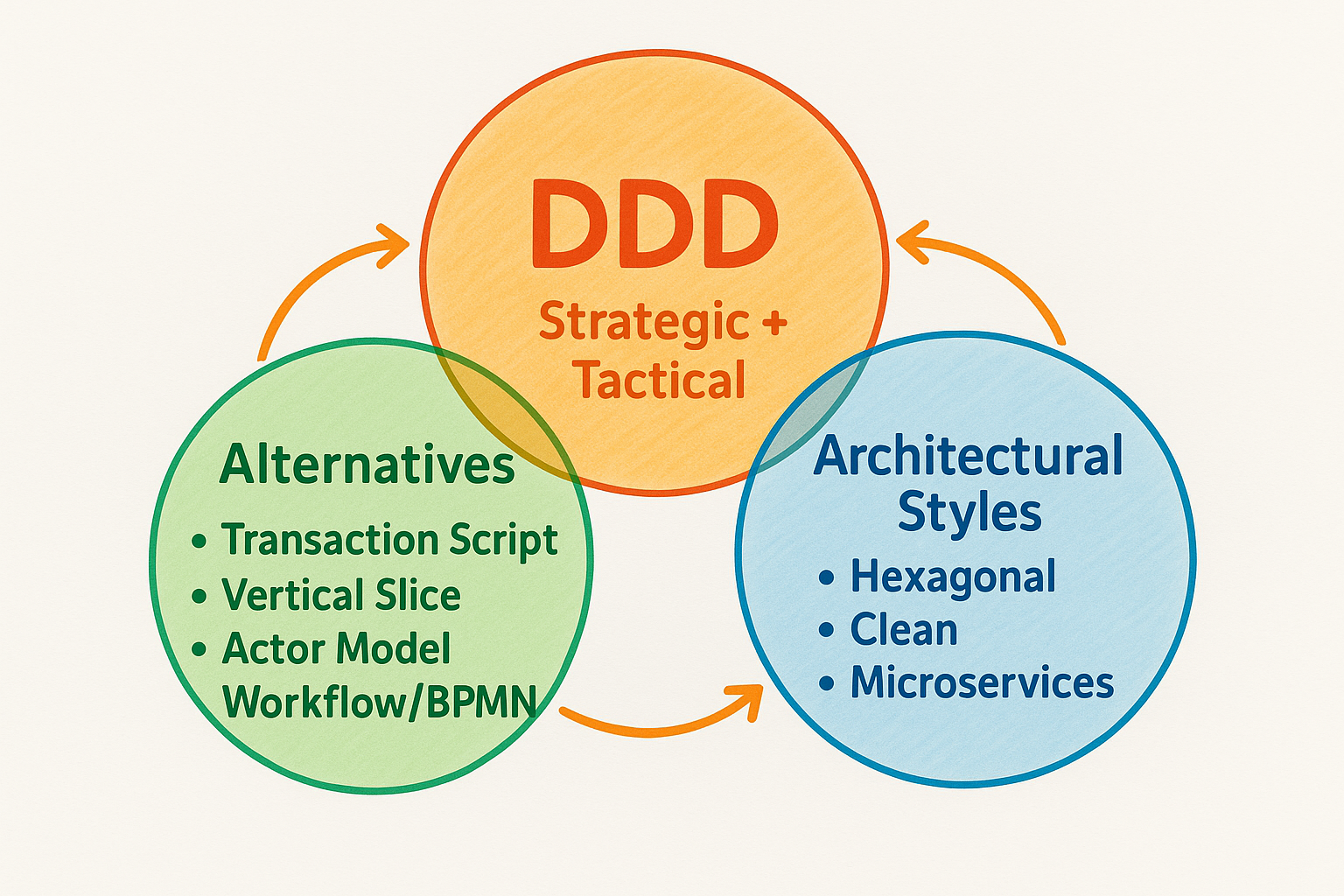

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) is a way of designing software by centering everything on the language and rules of the business. It gives you two kinds of tools:

- Strategic tools that help you draw the map of the problem: shared language, clear boundaries between sub-domains (bounded contexts), and how those pieces talk.

- Tactical tools that help you shape the code inside a boundary: entities, value objects, aggregates, domain services, domain events, repositories, and so on.

Think of it like city planning vs. building a house. The plan (streets, zoning) is strategic. The house (rooms, plumbing) is tactical. DDD does both.

Why DDD is not just the tactical part

Many teams “do DDD” by sprinkling Aggregate and Repository classes into a codebase. That’s like putting crown molding on a tent.

The real power shows up before code: agreeing on words that mean the same thing across business and tech, and cutting clean boundaries so sales, pricing, payments, delivery, and reporting don’t trip over each other. The tactical pieces only make sense inside those clean boundaries.

What DDD is not

- Not an architectural style. You can practice DDD on top of Layered, Hexagonal/Ports-and-Adapters, Onion, Clean Architecture, a well-structured monolith, or microservices.

- Not a silver bullet. If your domain is simple, DDD can be overkill.

- Not “just rich entities.” Rich models without a shared language and boundaries become heavy, not helpful.

- Not “use events everywhere.” Domain events are a tool, not a religion.

DDD’s place among architectures and patterns

Architecture is the stage (Layered, Hexagonal, Clean, Microservices). DDD is the script and director’s notes you choose to use on that stage.

You might use Hexagonal to keep I/O at the edges, and DDD to keep the core honest. Or you might skip DDD entirely and run fast with transaction scripts in a simple service. Both are legitimate choices.

When to practice DDD (the “messy-domain” moments)

Use DDD when the language is contested and the rules keep changing, yet invariants must hold. A few lived-in examples:

- Marketplace orders & fulfillment. One order touches merchant inventory, courier assignment, customer updates, payments, refunds, SLAs. Invariants like “an order can’t be both cancelled and out-for-delivery” matter. DDD helps you split Ordering, Fulfillment, Delivery, and Payments, each with its own language and rules, and coordinate them safely.

- Promotions & pricing. “Buy 2 get 1,” city-only discounts, wallet credits, per-user caps, finance audits. DDD lets you model rules as first-class concepts (value objects, policies) and keeps Pricing from leaking into Orders.

- Payments & settlements. Multiple PSPs, retries, idempotency, chargebacks, daily payouts. DDD protects legal state transitions inside a Payments context and shields the core from gateway quirks with anti-corruption layers.

- Ledger & accounting. Auditable double-entry postings derived from business events. DDD keeps money logic explicit and tamper-proof.

- Inventory reservations. Holds, expirations, back-orders, substitutions, race conditions. DDD lets a Reservation aggregate enforce “no negative stock” while the rest of the system stays decoupled.

If you’re regularly drawing state machines on a whiteboard and arguing over vocabulary, you’re in DDD country.

When not to practice DDD (and lighter, sane alternatives)

Not every app is a hospital; sometimes you’re building a kiosk. Reach for the lightest tool that preserves correctness.

- Straightforward CRUD/admin portals. Keep it simple with transaction scripts (one handler per use case). In .NET this can be Minimal APIs or MediatR handlers that validate → fetch → compute → save.

- Data-centric internal tools. Use Active Record/Table Module style or an anemic model with a thin service layer. Close to the database, easy to reason about.

- Product teams optimizing for speed. Use Vertical Slice (feature folders, one request = one handler + validation + persistence). Strong cohesion, fast onboarding.

- I/O churn, stable core. Choose Hexagonal/Clean for ports/adapters to protect the core - but the core can still be simple transaction scripts if the domain is simple.

- Workflow-heavy, long-running processes. Use a workflow engine (BPMN/Temporal/Durable Functions). Put the business flow at the center; keep step logic small and explicit.

- Integration-first platforms. Go API-First/Schema-First (OpenAPI/AsyncAPI) and generate contracts. Let the schema lead.

- Reactive glue with thin rules. Use event-driven designs without rich aggregates; keep models local and light.

- Actor model with simple per-actor logic. If each “thing” (cart, device, user session, driver) has mostly isolated state and rules - no heavy cross-entity invariants - an actor system (per-actor mailbox + state + timers) is perfect. Each actor stays simple; the runtime gives you concurrency, timers, and resilience. You avoid the ceremony of aggregates while still staying correct.

A good heuristic: if your “why this is hard” list is mostly process and I/O, don’t pay the DDD tax. If it’s mostly business language and rules, DDD earns its keep.

A closing story

Teams get into trouble when they treat DDD like a badge. The better move is humbler: sit with the business, argue kindly about words until they mean one thing, draw boundaries that match how the work actually flows, and then pick the simplest code style that won’t lie to you six months later.

Sometimes that’s DDD. Sometimes it’s a clean slice with a single handler. Sometimes it’s a little army of tiny actors minding their own business.

Choose the lightest thing that keeps the truth intact.